The Staying Power of John Adams

INTERVIEW | The composer reflects on "Frenzy", "City Noir", and why contemporary music is beginning to atrophy

WORDS BY STEPHANIA ROMANIUK

ILLUSTRATION BY DANE THIBEAULT

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MUSACCHIO IANNIELLO PASQUALINI

INTERVIEW BY MICHAEL ZARATHUS-COOK

ILLUSTRATION BY DANE THIBEAULT

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MUSACCHIO IANNIELLO PASQUALINI

INTERVIEW BY MICHAEL ZARATHUS-COOK

The Canadian premiere of John Adams’s latest orchestral piece Frenzy will take place during election week in the US—coincidental, and perhaps fitting for a composer whose works regularly respond to inflection points in American politics. Operas like Nixon in China, the controversial The Death of Klinghoffer, and Doctor Atomic (about J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project), and the Pulitzer Prize-winning choral-orchestral work On the Transmigration of Souls (in response to 9/11) explore figures within the events themselves, but also serve as large-scale reactions to some of the most highly charged times in American history. Now one of the world’s most celebrated and regularly performed contemporary composers, Adams will also be conducting the performance. At the podium, not only can he explore the needs of the work more fully, but performing the piece also fulfills for him music’s ultimate aim: communication.

For 50 years, Adams has worked to dispel the notion that great art must be aloof and inaccessible. Although few would consider Adams a crossover artist, he writes music that is connected to popular forms, to repeating rhythms, and to the tonality first deconstructed by the Second Viennese School and still often disfavoured in academia. Influenced as much by orchestral giants Beethoven and Sibelius as by the minimalists Terry Riley and Philip Glass, the jazz of Miles Davis, the soul of Aretha Franklin, Broadway, and the dance halls of his youth in rural Massachusetts, Adams has built a sound of his own—pulsating and orchestral—that is heard live internationally nearly every day of the calendar. His sound stands firmly in the American tradition of the Gershwins, Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, and yet continues to develop.

With Frenzy, Adams shifts from his minimalist roots to explore melody and development. In compositional terms, he uses techniques new to him but typical of the Classical masters: Fortspinnung and Durchführung, German terms for “spinning out” and “through-leading.” Together, they represent taking a melodic idea and transforming it through progressive development. The first four notes of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 are introduced and then transformed throughout the orchestral work using this approach. Although no recording of Frenzy exists yet, music history survey courses covering the 20th and 21st centuries may likely include the work as an example of traditional practices resurfacing in contemporary works. (Perhaps Adams’s melodic interest may foreshadow a shift also in popular vocal music toward melody, conspicuously underutilized since roughly the late-1990s.)

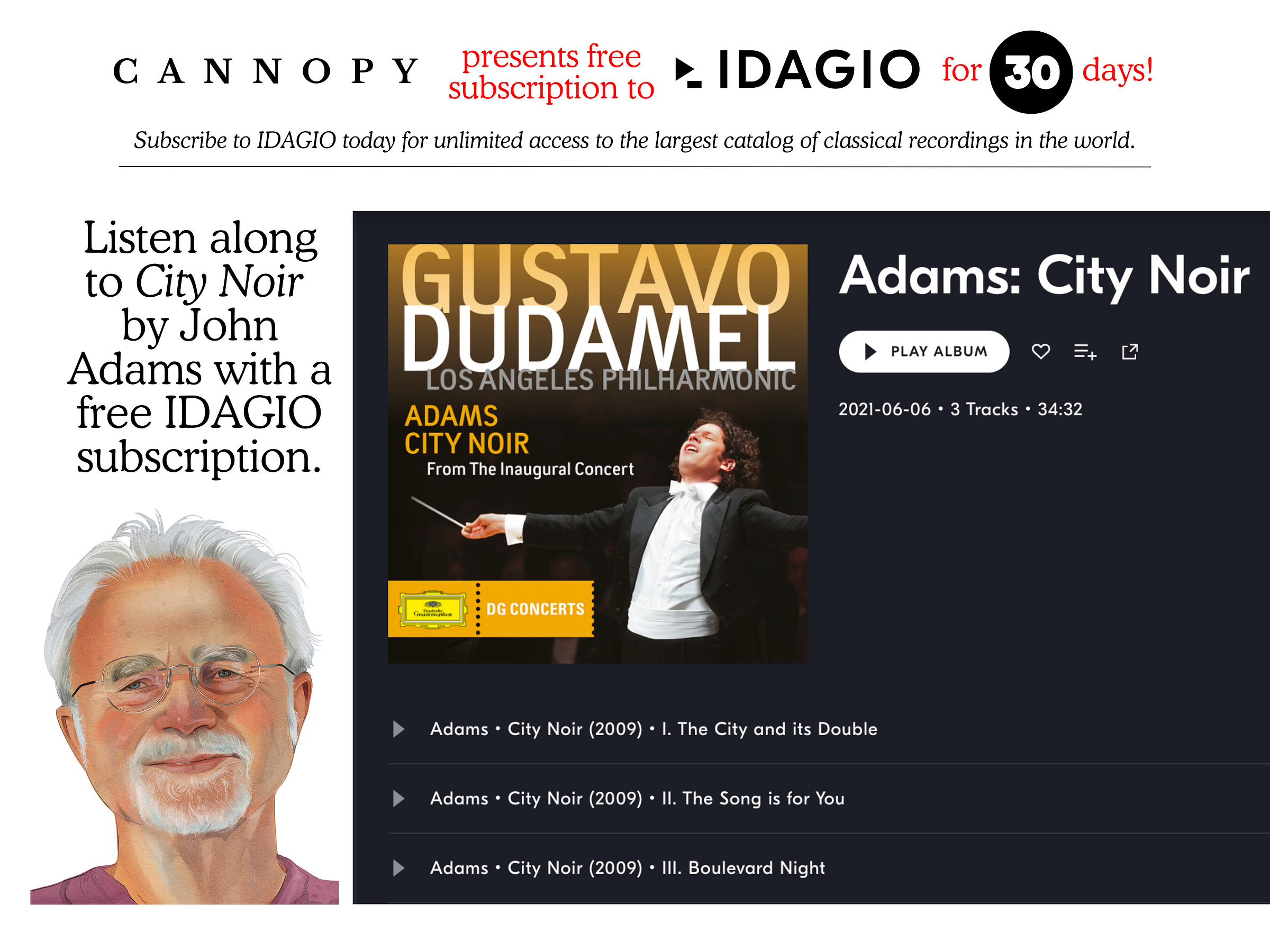

Another notable upcoming performance includes City Noir with the New York Philharmonic, a tribute to Los Angeles and the gritty film noir of the 1940s, 50s and beyond. A symphonic expansion of the moody, raucous incidental music characteristic of these films, as well as a tribute to a great, “imagined,” city, the work was written for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, where Adams has held the role of Creative Chair since 2009. Under his tenure, important works by composers including Steve Reich, Gabriella Smith, Louis Andriessen, and Andreia Pinto Correia have been premiered, as well as many of Adams’s own works, including the piano concerto Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes? This position has served as one of the many platforms, including the Pacific Harmony Foundation, John Adams Young Composers program, and residencies with the Juilliard School and Berliner Philharmoniker Akadamie, Adams uses to inspire and mentor upcoming composers seeking to understand, write for, and connect with contemporary audiences and performing arts institutions.

The staying power of Adams’s own output, particularly the large orchestral and operatic works, shows that humans arguably connect more readily not with a purely cerebral sound, but with one that’s embodied. (Adams’s latest opera, Antony and Cleopatra, returns this season to The Metropolitan Opera, and Nixon in China, Doctor Atomic Symphony, and the opera-oratorio El Niño will all be heard elsewhere.) Large institutions need certainty, and Adams’s works are predictable in their appeal. Regardless of subject matter, Adams’s music, often described as “humanist,” tends to feel sturdy, present, and an integrated whole. Music that, in his words, becomes too “self-referential” disconnects itself from the familiar, inherited ways we understand and find meaning in music—the lullabies, dances, ballads, laments, and archetypal forms that exist in all cultures across all times, which Adams has successfully incorporated into his vocabulary. With Adams, perhaps therapy can be found in listening even to the chaotic, the frenzied—at least when expressed through the not-yet-outdated architecture of melody, tonality, and line.

For additional listening, consider Fearful Symmetries (an orchestra outpouring in the vein of Nixon in China) and The Wound-Dresser (for baritone and chamber orchestra on the poetry of Walt Whitman), as well as one last nudge to listen to the delicious and unique City Noir.

INTERVIEW WITH JOHN ADAMS

Enjoy what you’re reading here? Consider subscribing to our other platforms:

Performing Arts | Visual Arts | Soundstage Arts | Alternative Arts